Enhanced protection

24-hour prevention

Mitigate resistance

Highly adaptable

Spatial repellents, sometimes called spatial emanators, are a new class of vector control intervention designed to complement insecticide-treated mosquito nets or indoor residual spraying and protect people from malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases. There is also hope that spatial repellents could provide protection when deployed on their own or in settings where coverage with other vector control interventions is low.

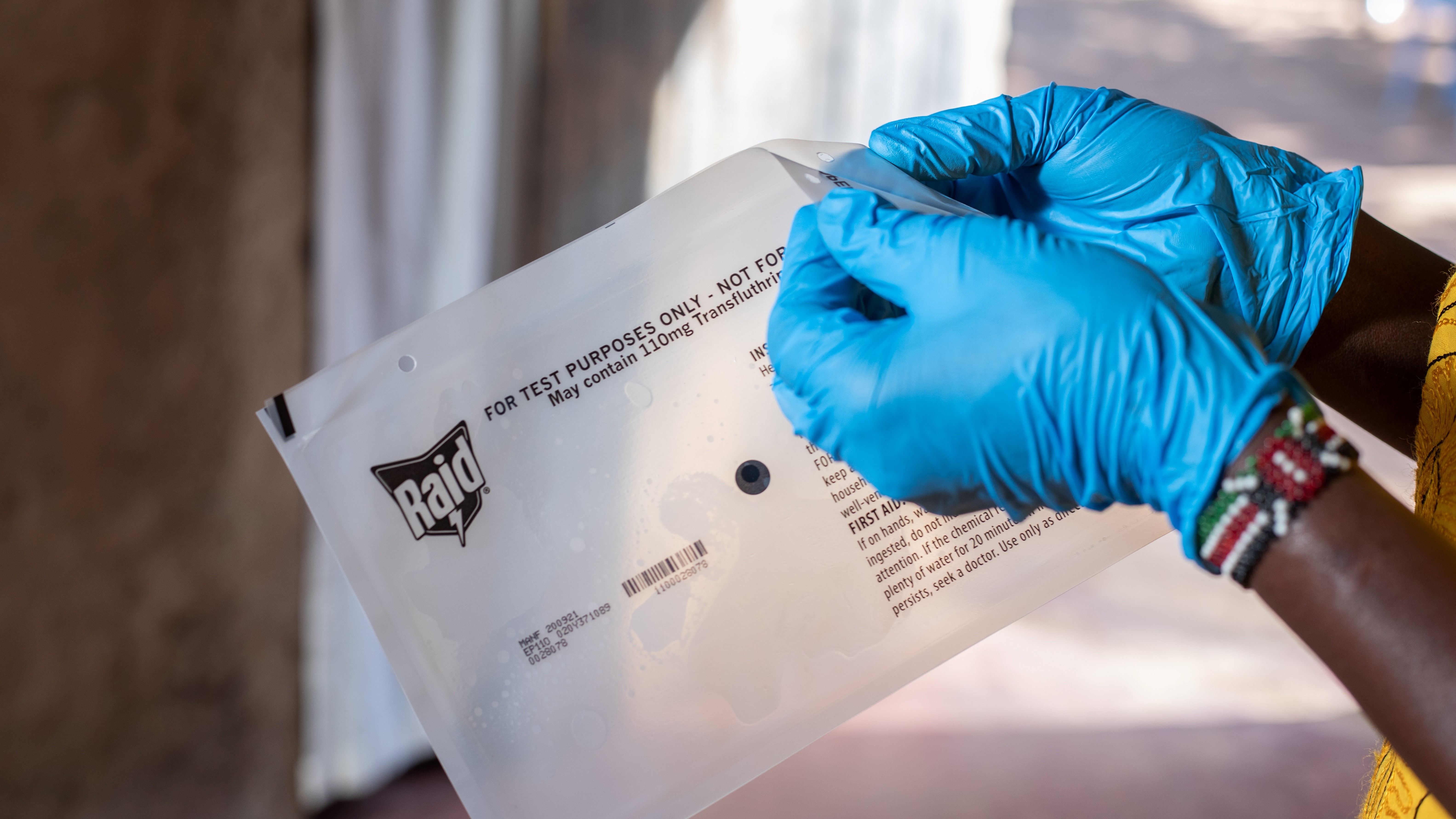

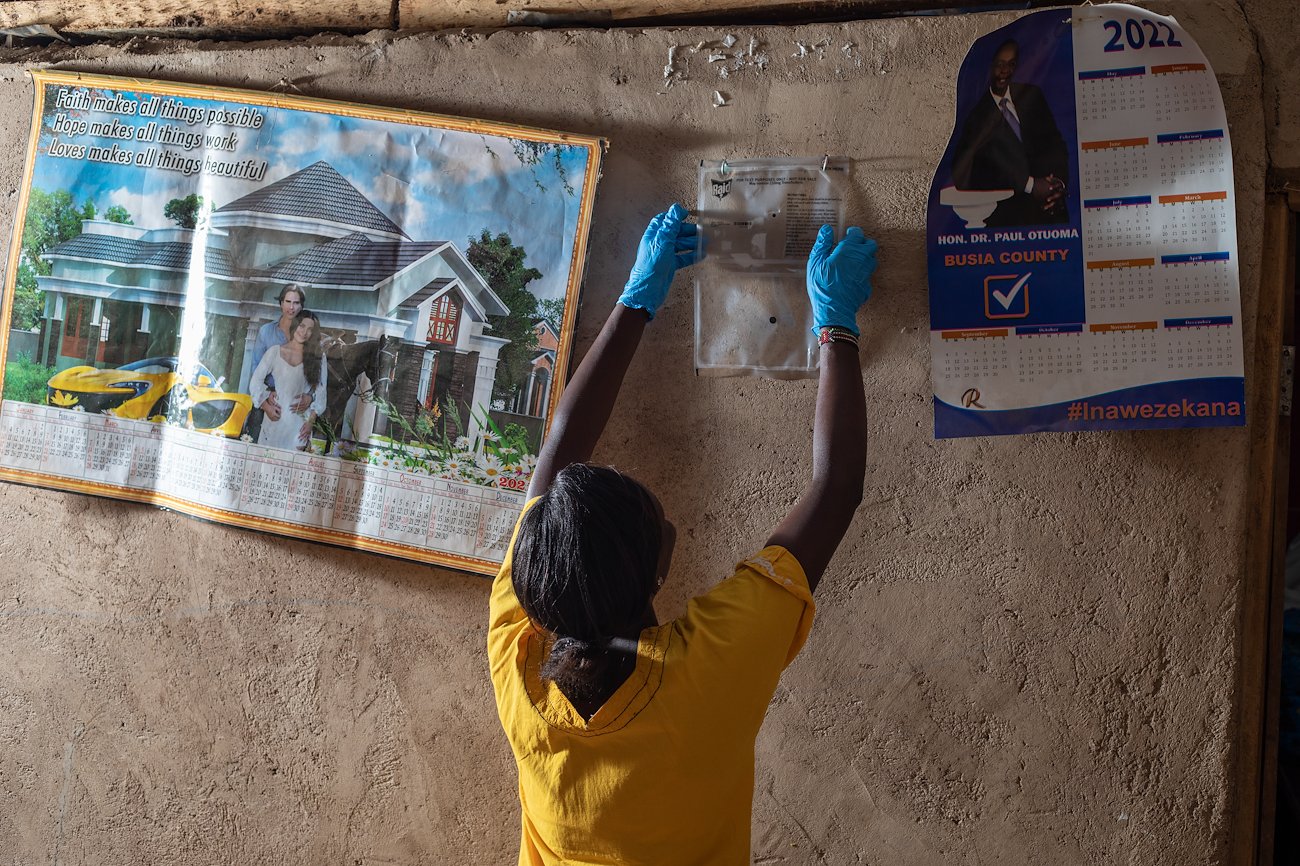

Made of a thin sheet of plastic or mesh on a frame smaller than a standard sheet of paper, they hang on the wall and slowly release chemicals into the air. These chemicals repel mosquitoes and prevent them from biting people. They may also kill the mosquitoes or impact their reproductive behavior which, when coverage is high, could reduce mosquito populations and provide disease prevention to a whole community.

Insecticide-treated nets are by far the most widely used vector control intervention but resistance to the key insecticide used on them – pyrethroids – has impacted their efficacy. As nets are used in close contact with people and over many years, the choice of safe and sufficiently durable insecticides is extremely limited. Developing new insecticides to keep ahead of resistance has proven to be a costly, complex and lengthy process. Additionally, mosquitoes have adapted to wide-scale net use, with more biting happening earlier in the evening when a person may not be sleeping under a net.

Indoor residual spraying can be logistically challenging, particularly in remote areas, and reaching the required coverage rates over successive spray rounds may be challenging due to household refusal.

Spatial repellents, which are compact and easier to transport than nets or spray equipment, could be a cost-effective complementary, or even alternative, intervention. They may prove effective in settings where deploying nets or sprays is challenging, such as in humanitarian crises where there may not be structures to spray or hang nets, or in settings such as urban environments where the uptake of conventional vector control interventions has been low. Because spatial repellents provide around-the-clock indoor protection, they are also likely to protect people from mosquitoes that primarily bite during the day, such as the Aedes mosquito, which transmits dengue and other viruses like yellow fever, zika and chikungunya.

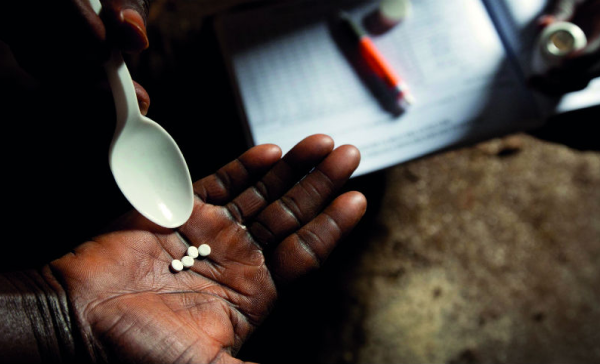

Spatial repellents have shown promising initial results in reducing mosquito bites and malaria transmission when used in combination with mosquito nets. A Unitaid-funded trial in Kenya was the first to show the significant impact of spatial repellents against malaria, reducing infections by one-third. Additional Unitaid-backed research trials in Mali and Sri Lanka are investigating the product’s efficacy against malaria and dengue, respectively. This work builds on previous trials: one in Indonesia that suggested a positive impact on malaria and another in Peru that found that spatial repellents reduced the risk of dengue infection by 34%.

We are supporting research to validate the efficacy of spatial repellents in combatting malaria and dengue, with clinical trials in Kenya, Mali and Sri Lanka under the AEGIS project, led by the University of Notre Dame. The trial data will inform the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guideline development process, aimed at developing recommendations for new public health interventions. Additional Unitaid investments will further expand the evidence base on spatial repellents and close remaining evidence gaps, as identified by WHO.

In parallel, we are working with industry, procurers and implementing partners to assess barriers related to supply and demand of spatial repellents and design market-shaping interventions to overcome them, helping lay the groundwork for the scale-up of this new vector control intervention.